Over the past years, the trend in storage speed can be summarised as: faster CPUs with DRAM unable to keep up, resulting in a widening CPU/memory gap. Even as clock speeds have mostly steadied by 2003, the increasing use of multi-processors means higher throughput (or, effective cycle time, i.e. cycle time divided by the number of cores), even as latency decreases have stagnated. So the gap remains.

An interesting effect is that high CPU utilization often just means the processor is stalled due to slow memory I/O. To alleviate this bottleneck, CPU manufacturers have added layers of cache between the CPU and main memory, usually L1 and L2, but sometimes L3 and even L4 in rare cases. Since caches reside on-chip, the hope is that we avoid an expensive round-trip across the memory bus.

But caches are not perfect. For one, caches, unlike CPU registers, have low granularity - usually 64 bytes for a single cache line[1]. So reading a single 4-byte integer from memory will result in pulling in an excessive 60 bytes into the cache.

Another effect is that if two pieces of data live in the same cache line and are modified simultaneously by multiple cores, each core will evict that corresponding cache line on every other core, a phenomenon known as false sharing.

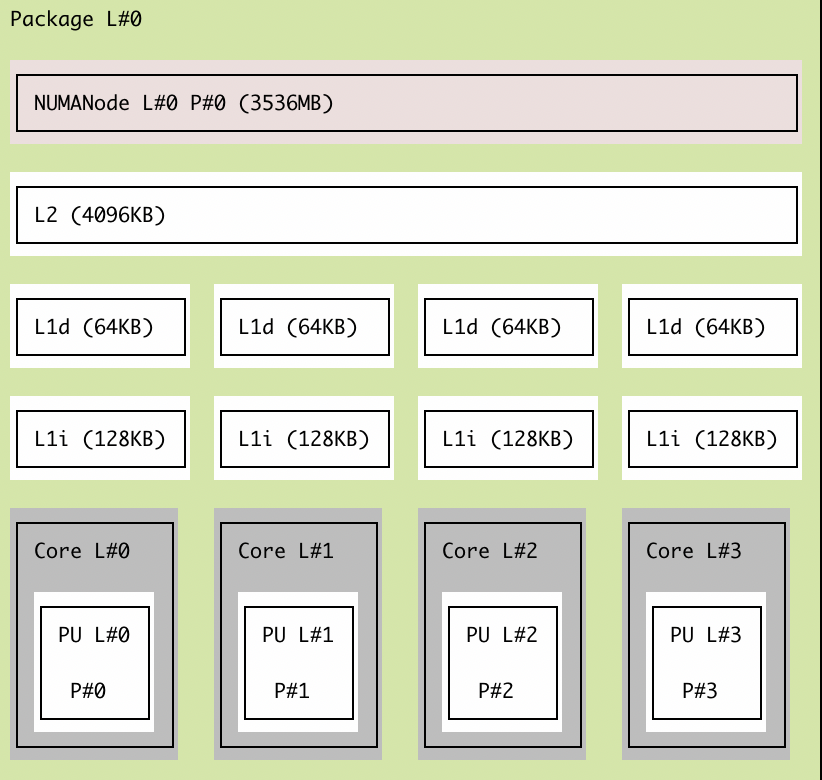

An example memory hierarchy can be seen below[2].

Each core has its own L1 cache but share a single L2 layer which sits between the L1 caches and main memory. Since L1 caches are per-core, we need to make sure they are consistent with each other - this is referred to as cache coherency.

The use of individual L1 caches leads to the problem of false sharing described previously.

Imagine two cores modifying variables a and b. Core 1 exclusively modifies a, while core 2 exclusively modifies b, so there is no potential for a race condition. However, the two variables happen to reside on the same cache line. So what happens is every time core 1 modifies a, core 2’s cache gets invalidated. Thus, when core 2 attempts to read a previously cached b, a cache miss occurs, causing core 2 to need to fetch from L2. The sequence can be illustrated below, using the MESI protocol.

| time | action | core1 | core2 |

| 0 | - | shared, a:0, b:1 | shared, a:0, b:1 |

| 1 | core1: write a++ | exclusive, a:1, b:1 | invalid, a:0, b:1 |

| 2 | core2: read b | shared, a:1, b:1 | shared, a:1, b:1 |

| 3 | core2: write b++ | invalid, a:1, b:1 | exclusive, a:1, b:2 |

| 4 | core1: read a | shared, a:1, b:2 | shared, a:1, b:2 |

Note that between t = 1 and t = 2, core 2’s value of b does not change, meaning it went all the way to L2 to fetch the same value it already had in L1. Even if b is present in the shared L2 cache, it still takes around 10 cycles, compared to ~4 cycles for L1. Reading from memory would take 200 cycles.

Notice that in the above example, the shared L2 cache acts like a backstop for the extra traffic we incurred, preventing us from moving further down the memory hierarchy and wasting more cycles. If we had per core L2 caches, or if our two cores happened to be assigned to different L2 caches, the false sharing problem would continue to propogate until we find a common storage layer, either L3 or main memory.

Demo

Let’s see how false sharing can impact your program in practice. First, we allocate a struct with two variables a and b. Since they are contiguous in memory, we can expect them to reside on the same cache line. Then, we create a function that updates either a or b a large number of times.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <pthread.h>

long NUM_ITER = 3l * 1000l * 1000l * 1000l; //3 billion

typedef struct {

int a;

int b;

} Foo;

Foo foo = {0, 0};

void *increment(void *var) {

char *c = (char*)var;

for (size_t i = 0; i < NUM_ITER; ++i) {

if (*c == 'a') {

foo.a++;

} else if (*c == 'b') {

foo.b++;

}

}

return NULL;

}

Here is the main method that creates one thread which updates a 3 billion times.

int main() {

pthread_t ta;

pthread_create(&ta, NULL, increment, (void*)"a");

pthread_join(ta, NULL);

return 0;

}

Running the above code and time‘ing it takes a little under 6s:

$ gcc main.c -o main && time ./main

real 0m5.662s

user 0m5.605s

sys 0m0.002s

What if we add a second thread that does the same to b? Since thread 1 updates a and thread 2 updates b, we should expect the time to remain the same, as we can utilise two cores in parallel. Our main method now looks like this:

int main() {

pthread_t ta;

pthread_t tb;

pthread_create(&ta, NULL, increment, (void*)"a");

pthread_create(&tb, NULL, increment, (void*)"b");

pthread_join(ta, NULL);

pthread_join(tb, NULL);

return 0;

}

But upon rerunning it we see the real time go up to ~18s. This is because we’re seeing false sharing in action!

To resolve this issue, we can pad the struct, making sure that the two variables reside at least 64 bytes apart. So here we need 60 bytes of padding, which can be done with 7 doubles and an additional int.

typedef struct {

int a; // 4

double d1,d2,d3,d4,d5,d6,d7; // 56

int i1; // 4

int b;

} FooPadded;

FooPadded foo_padded = {0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0, 0};

Running a single thread takes around the same time as before (~5.4s), but with two threads:

$ gcc main.c -o main && time ./main

real 0m6.493s

user 0m11.915s

sys 0m0.003s

We’re now down to ~6s, which compared to 18s is a 3x improvement! From the output above, you can see we are taking advantage of parallelism. The user row, which shows the total time spent in userspace, is about twice our elapsed system time, meaning two cores are simultaneously running.

You can moreover see that our latency now does not increase with the number of threads (the small increase is probably due to the small overhead of starting the thread). You can try bumping up the number of variables and threads (up to the number of cores you have) to verify that the time remains roughly constant.